Archie wrote: ↑Thu Nov 14, 2024 2:49 am

The Red Cross was Mr. Magoo. And the Vatican was Mr. Magoo. And the US State Department was Mr. Magoo. And the British Foreign Office was Mr. Magoo. And the New York Times. At some point we have to conclude that there wasn't anything to see.

The flaw with most of the wartime knowledge literature is that they equate receiving a "report," even an absurd one, with having "knowledge" about "the Holocaust" even when it's clear the entities in question didn't take the "reports" at face value.

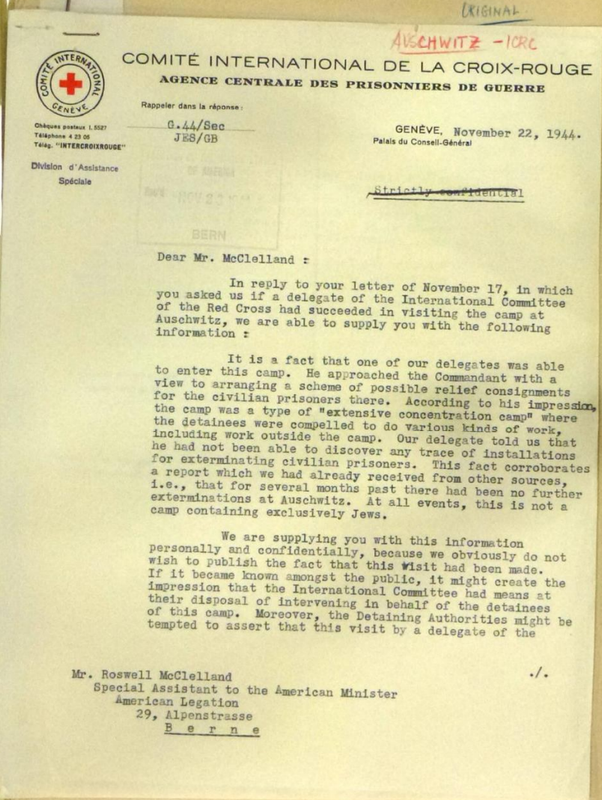

No, the ICRC received plenty of reports of extermination and gassing, and evidently believed them. I noted one example from the delegate in Budapest who was replaced in mid-May 1944 by a German speaker (a better choice now the Germans had occupied the country) who came back having heard from Hungarians as well as Hungarian Jewish leaders in May 1944 that deportees to Poland were being gassed.

Rossel was Mr Magoo, but the Magoo-like aspects were in part down to being a neutral and not wishing to offend the Germans. The ICRC as an institution emphasised its neutrality, and could come across as terrifyingly disengaged as a result, a point made several times in Jean-Claude Favez's book, which I looked at again last night after this came up.

The Vatican's secretary of state acted in a similar way, because of the imperative of neutrality. How the Vatican reacted is secondary to the significance of reports from nuncios but especially the cardinals, bishops and affiliated churches out in the occupied territories, as well as other Catholic priests who passed information on.

The metropolitan of Lviv, the head of the affiliated Uniate Church, Sheptytsky, wrote to the Vatican in 1942 speaking of hundreds of thousands of Jews killed. The Italian military chaplain Pirro Scavizzi directly informed Pius XII and his contemporary reports survive. They came through internal channels and are on a par with news spreading back to Germany for that reason, and on a par with the notes made by Axis diplomats likewise confirming a general policy of extermination. This could be inferred just from reports from the occupied Soviet Union of mass shootings.

The Vatican also received reports via the British and Polish ambassadors to the Holy See, and was further asked questions by Roosevelt's delegate Myron C Taylor in autumn 1942, to see if they could confirm reports that had already reached the US. The Vatican declined to confirm the reports based on its neutrality and stuck to that line through 1942-3. But the internal memos indicate that they had received accurate summaries of Polish government-in-exile reports in spring 1943 with Treblinka identified using gas (not steam). In 1944 the arrival of the Vrba-Wetzler report was delayed but this did not stop the Vatican after the fall of Rome from joining in the pressure on Horthy to stop the deportation of Hungarian Jews.

Neutrals like the Vatican, ICRC, Switzerland and Sweden were at pains to act neutrally so as not to alienate the Germans. The Swedes were the first to really 'act' by receiving Jewish refugees from Norway and Denmark, but all the neutrals were in on the rescue efforts in Hungary in 1944.

The US State Department and British Foreign Office both pursued foreign policies that did not recognise Jews as a national group and which strongly opposed Zionist arguments over opening up Palestine following the 1939 White Paper. This can be most clearly seen in the kicking of the rescue agitation into touch with the Bermuda conference, and with minor shenanigans that led to the eventual formation of the War Refugee Board. The diplomats also tended to oppose expansive prosecutions of war crimes thus hobbling the UN War Crimes Commission and restricting the mandate to crimes against Allied nationals, i.e. crimes against German and Austrian Jews were not being seriously considered for Allied war crimes prosecutions.

Despite this, in autumn 1942 enough reports accumulated to overrule the diplomats and make the UN declaration on the extermination of the Jews of December 17, 1942 possible. The State Department watered down the language to 'be on the safe side', but this represents typical caution and also makes the wailing from revisionists less plausible.

Allied diplomacy had to contend with multiple governments-in-exile who were keen to publicise the postwar punishment of war criminals already in 1941-2, cueing off the increased rate of general reprisals in late 1941. Thus the St James Palace meeting and declaration. The WJC was miffed not to be included, but its own diplomacy to achieve recognition of Jews as a nationality, co-combatant, co-plaintiff consistently failed all the way through to 1945.

The governments-in-exile were also major sources for publicity in 1942 and beyond. An analysis of wartime public reports makes this clear, they were at least as significant as Jewish organisations, with some like Ignacy Schwarzbart straddling the roles. But unless Schwarzbart received something via underground channels from the Bund in Poland, he was dependent on Polish government-in-exile reports.

The literature on wartime knowledge has long distinguished between knowledge and comprehension or belief. It is certainly very easy to overinterpret the transmission of reports as meaning instant acceptance, when this is demonstrably not the case. Hindsight also reveals many more reports travelling in different directions which cannot have all been known to any one person or institution or outpost/embassy etc.

Both the neutrals and Allies had strong interests in downplaying the reports, the neutrals to remain neutral and the western Allies to maintain their basic foreign policy positions especially regarding Palestine. This also extended by 1943 to needing to rein in the Polish government-in-exile and not jeopardise the Grand Alliance, which meant disregarding Polish claims to eastern Poland against the Soviet assertion of the Curzon Line and 1939-41 borders. The post-Katyn breaking off of Soviet-Polish relations really did not help, either. This is one possible reason why various reports received in 1943 were not given the same publicity as the late 1942 reports, not because they were as such disbelieved, but because they were arriving in an awkward time.

But this did not stop a general groundswell of publicised reports, which in turn became known to the RSHA and German Foreign Office. In 1943-44 the Welt-Dienst was translating articles from the New York Yiddish newspaper Forwerts, whose contents are usually recognisable as Jewish Telegraphic Agency reports or ones that had reached Sweden, Switzerland or the Balkans then Palestine from fugitives. This was the hidden flood of reporting that grew in 1943-45. The Jewish Agency circulated bulletins reproducing such accounts and these also show a publicising of other known fugitive reports.