Here is an article by Stanisława Lewandowska called "Z fałszywym Ausweisem...".

https://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media/texts/roc ... s75-90.pdf

It has a lot to say about how forgeries were produced, although I haven't gleaned much from it. Signatures and stamps are mentioned. Document ID numbers are not. Dates are mentioned just once, translated below.

[...] required the immediate possession of fictitious documents, which were produced by the Kedyw legalization unit of the Home Army Headquarters [komórka legalizacyjna Kedywu KG AK]. Obtaining them required completing formalities specified in this unit's guidelines. They read:

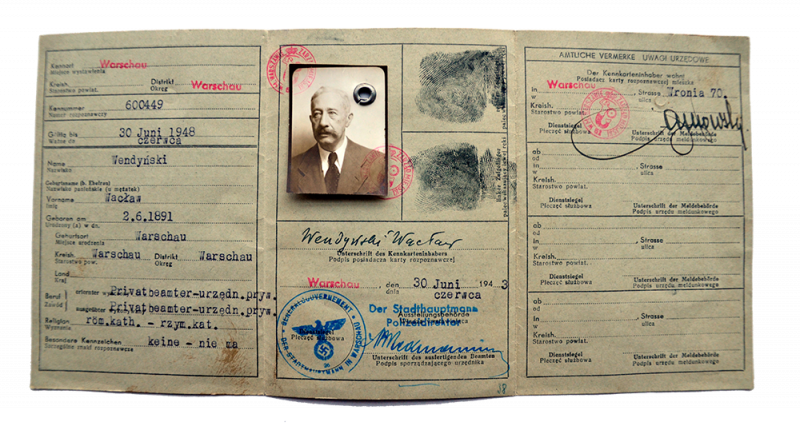

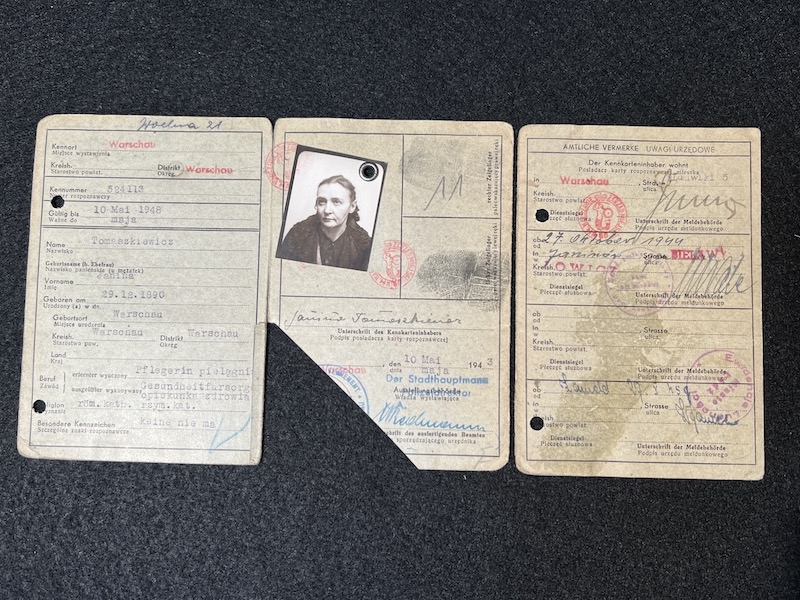

When ordering documents, please indicate whether the address is real or fake. On order forms, in the place of residence box, we have two capital letters R and L. If the address is real, circle the letter L, and if it is fictitious, circle the letter R. When ordering a "KR" [karta rozpoznawcza, or identity card] from Warsaw with a real address, please provide at least an approximate date of registration, in order to properly match the dates in the "KR." When ordering a "KR" with a fake address, please indicate whether it could be a "KR" from the provinces, re-registered to Warsaw. Please prepare orders legibly and understandably; unclear orders cause delays in their execution

So the Polish resistance at least had a formalized process for producing inauthentic Kennkarten, and they did have some awareness of how to correctly forge a date. This makes it more plausible that Wiernik's card was forged from scratch.

I'm now reading through

Kryptonim 'Zegota'. Despite the name, a substantial part of this book is merely a conventional historybook on the Holocaust. Jews good, Poles bad, Germans worse, 4M at Auschwitz, etc. Where it starts to become useful is with names and addresses. I'm not sure if we already had this information (p.84):

Another example of dedicated and effective participation in the "Żegota" campaign is the activity of Andrzej Klimowicz, a member of the left-wing youth movement and the underground Democratic Party. [...] His tire repair shop in Warsaw at ul. Nowy Świat 41 was a place of lively underground contacts, ad hoc support, as well as a temporary hiding place and information and intelligence point. "This location," wrote Irena Sendler, "was: 1) the contact point for the Three Żegota activists—Adolf Berman (alias Borowski, Adam from Poale Zion), Leon Feiner (alias Mikołaj from the Bund) and Fiszgrund Salo (alias Henryk, also from the Bund), 2) a mailbox for the transfer of documents, addresses, and money from Żegota to the persecuted, 3) a place for a group of wards, who were hiding Jews under the constant care of A. Klimowicz. Through him, they received the necessary documents, addresses of apartments, hiding places, money, and contacts for transfers to the partisans. Among others, this location was used for a long time, hidden behind a partition in the workshop, by Mr. Wiernik Jankiel, a carpenter by trade who escaped from Treblinka.["]

I find it pretty remarkable that Wiernik was actually residing at what could probably be termed the headquarters for Zegota. This same address then appears again as the center for printing forgeries (p.87):

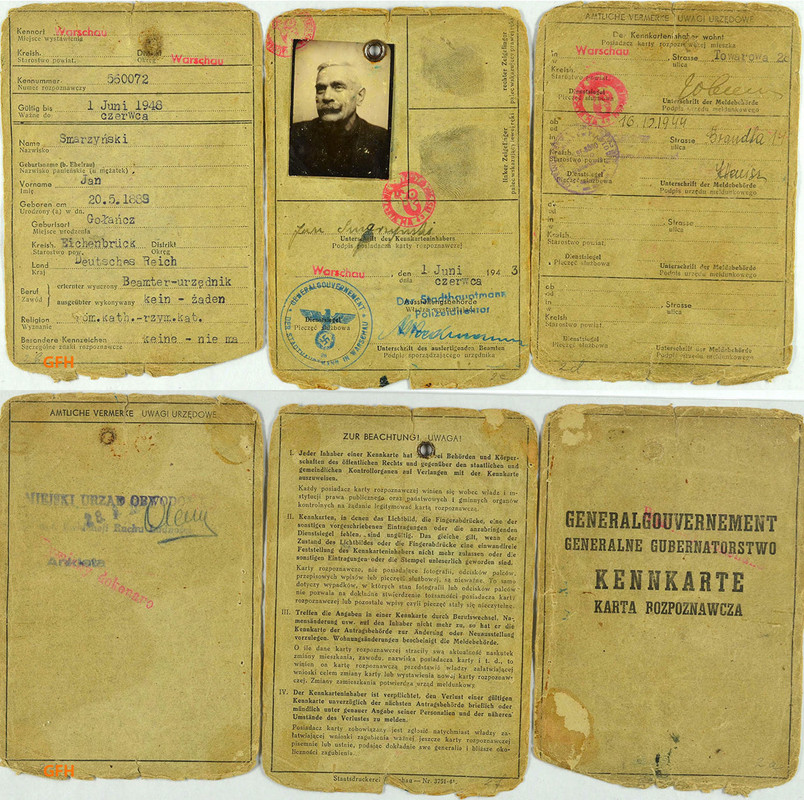

The legalization [forgery] office consisted of six people permanently employed by the Council. It was headed by Leon Weiss ("Leon"). It prepared various personal documents, including Kennkartes, Arbeitskartes, Ausweiss, various service IDs (including those for SS and Gestapo officers), birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates, residence card stubs, passes, and various other forms. The forgeries were produced with great precision and generally made it impossible to determine their authenticity. They were prepared on original copies from the relevant offices, usually obtained through bribery. When bribery failed, samples of the originals were photographed and documents were then produced on appropriate quality paper, acquired with considerable difficulty. Printing took place at the secret printing house of the Democratic Party (ul. Nowy Świat 41).

The authors then mention forging seals and signatures as well as the process of getting some of these fake identities entered into the German registration system.

The authors also add that for Zegota "all legalization services were free of charge," (p.88) which is contrary to my argument above.

Possibly we could argue that the claims made throughout this book are not credible, lacking proof, and somewhat outlandish, but there is not a lot of motive to exaggerate these things. If we take their claims as true, then it is likely Wiernik's Kennkarte was an expert forgery which was merely backdated several months.