The historicity of "blood libel"/ritual murder

Posted: Sun Oct 19, 2025 7:14 pm

This topic has been mentioned here and there on the forum, but I don't think we have a dedicated thread for it yet. Recently I was reading up on it a bit as part of my October/Halloween reading, so I figured I would start a thread for it while some of it was still fresh in mind.

One thing that interests me very much about this topic (aside from it being inherently lurid and sensational) is that it creates some curious conflicts for both Jews and revisionists. If you read the Jewish apologetics on this topic, they argue that the Jews who confessed and were convicted of ritual murder were victims of coercion and that the trials were akin to witch trials. This is noticeably similar to argument revisionists make against Nuremberg and against the Holocaust. It is amusing that in this context (where they have an interest in debunking rather than defending a disputed legend) they argue in revisionist fashion for the exact sort of widespread conspiracy/mass delusion (show trials, false testimonies) that they claim is impossible in the context of the Holocaust. Similarly, for revisionists, our rationalist impulses should incline us toward skepticism of these child sacrifice stories. However, Holocaust revisionists also tend to be rightfully wary of Jewish historiography, and this "anti-Semitic" impulse in this case will push many in the opposite direction. While it may be tempting to accept the ritual murder stories essentially as a troll or just because it makes Jews mad, I think it's a very bad idea to fall into the trap of simply assuming anything damaging or embarrassing to Jews must be true, at least if you want to maintain your credibility.

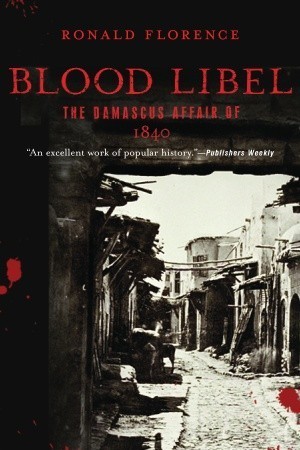

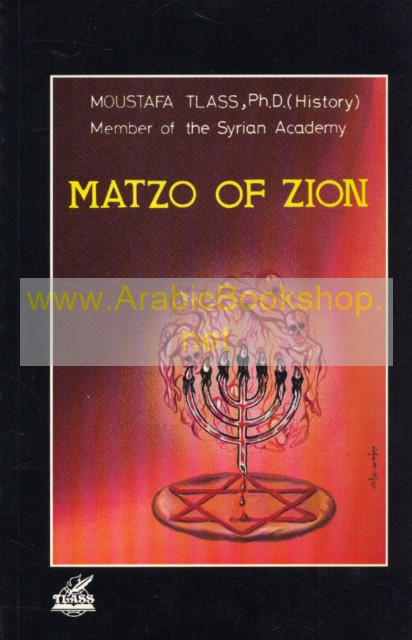

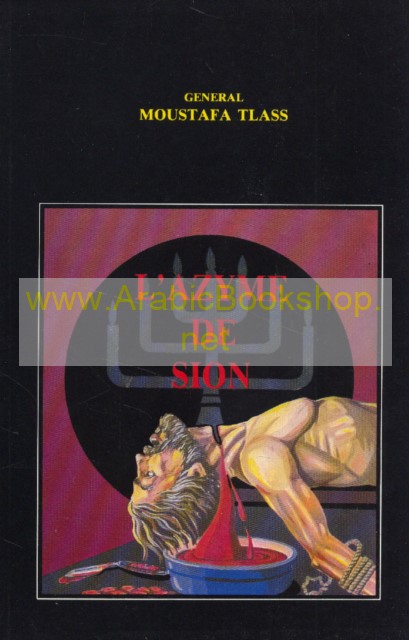

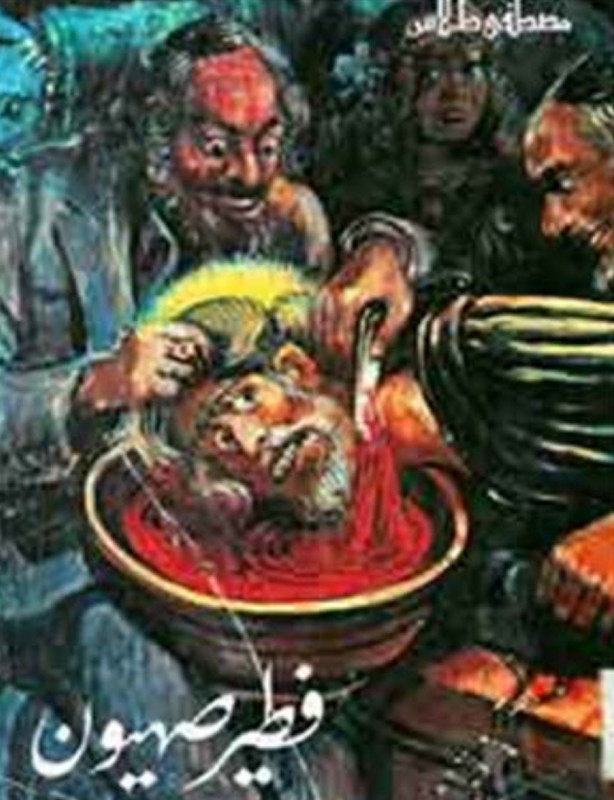

If you go back a few decades (before Ariel Toaff in 2007), it seems there was near universal agreement that the "blood libel" was mythical. In the 80s and 90s, it seems that revisionists and "scholarly anti-Semites" were not attempting to rehabilitate the story and were happy to let sleeping dogs lie. From what I can tell, you have to go back to pre-WWII where you see the idea promoted by personalities like Julius Streicher. Toaff has single-handedly revived the controversy however, and now it seems a number smart people such as Thomas Dalton and Ron Unz have been convinced to varying degrees of confidence.

Perry and Schweitzer (2002)

P&S have a book called Antisemitism: Myth and Hate from Antiquity to the Present. They dedicate a 30 page chapter to ritual murder allegation. I wanted to get an idea of the state of the debate pre-Toaff, and this 2002 book seemed like a good option. The chapter is heavily footnoted although P&S have done no primary research and are merely summarizing (pro-Jewish) secondary sources. But that is the sort of survey I was looking for. Below are what I've noted as their primary arguments.

1) In many of the blood libel cases, it indeed seems that the Jews were accused falsely. In some instances, it does seem that Jews probably were scapegoated. (It would take a long time to check up on the many individual cases they discuss.)

2) They highlight the magical and superstitious tendencies of Christians in Medieval Europe. Many of the accounts indeed seem fantastic and unbelievable to modern readers.

3) They argue all the Jewish confessions ("100% of the witnesses are wrong!" as Nessie would say, lol) are invalid because of coercion and torture.

4) They argue (and this is a very old argument) that the Torah prohibits use of blood etc (Lev 17:12) and that it is therefore unthinkable and self-contradictory to use unclean blood in a religious rite.

5) They produce quotes (some from the Middle Ages) from popes etc who have made various pro-Jewish statements dismissing the blood libel charge. (There have been Catholic authorities who believed it as well. The church formally repudiated as part of the Vatican II reforms).

I think the above is a fair recapitulation of the Jewish arguments on the matter as of the early 2000s. (I don't think there have been much if any updates to their talking points).

Something that stuck out to me as I read was that they leaned heavily on flattering the reader's presumed enlightened modern sensibilities as a contrast to the primitive superstitions of those dastardly medieval Christian bumpkins. Those goofy Christians actually believed that teh jooos broke into their churches and stabbed the communion wafers and that these wafers bled like Jesus. What a bunch of rubes! They love to pile on with this sort of thing yet they conspicuously avoid any discussion of what Jews at the time believed (the implication being that Jews were immune from such irrationalism). This omission is deliberate because once you realize that Jews also had a highly magical and superstitious worldview, the charge of bizarre Jewish rituals becomes more not less believable. In other words, this argument about magic and superstition is a double-edged sword. It may limit Christian credibility but it also increases the overall likelihood of weird beliefs and rituals among both Christians and Jews.

Toaff (2007)

Toaff's commentary is distinguished by the fact that he's done serious primary source research. He knows Latin and Hebrew and all that and he relies on original medieval sources rather than the sanitized history that is produced by modern Jewish scholars. I have not yet read Toaff's entire book. I read the preface (which I would very much recommend as a quick introduction) and chapter 6, "Magical and Therapeutic Uses of Blood." That chapter caught my eye because of its relevance to the very common it's-against-the-Torah argument.

Use of Blood and the Torah

Toaff demonstrates, I think rather conclusively, that Jews (or at least some Jews) did in fact use blood (usually in powdered form) for a variety of medicinal and ritualistic purposes. A famous example that is amazingly still practiced to some extent today is that the mohel during the circumcision ceremony will suck off the blood and foreskin from the baby. This contact with blood is apparently not considered unkosher or unclean. Even worse, apparently there is a documented variation of it where the mohel would spit out the blood into a glass of wine which is then given to the baby. Toaff even notes a documented custom (keep in mind many of these things were not universal among Jews) where women would fight over the bloody foreskin, based on the superstition that eating the male flesh would bless the woman with a male child (reminiscent of our tradition of the bride throwing out the wedding bouquet). In many cases, the sources for these sorts of things are Jewish converts to Christianity (whistleblowers, if you will), and Jewish academics as a rule dismiss these sources out of hand as automatic lies. But Toaff's citations include Jewish rabbis and other Jewish sources which seem more difficult to disregard. Toaff cites examples of books with recipes and potions involving blood, e.g. mixing powdered menstrual blood in wine and drinking it to treat heavy menstruation or using powdered menstrual blood of virgins mixed in wine to treat epilepsy. It seems there was a "market" for blood and some evidence that Jews would pay good prices for this blood. (In one of the blood libel trials, it seems the father killed his son, perhaps accidentally, while trying to extract blood from the neck. His story was that he intended to sell it to the Jews.) There is even some evidence that there were "kosher retailers" of this blood since fraud was common (trying to pass of animal blood as blood of a child).

Ah, but how do we square all of this with the supposed prohibition in the Torah? I didn't find the Torah argument convincing to begin with since legal rules are not much of a barrier to a people who are famous for creative and flexible legal interpretations (e.g.). Toaff helpfully confirms my suspicions by supplying direct examples of some of the many rationalizations (talmudry) that have been offered over the centuries.

-There are exceptions for cases of life and death (could justify some of the health usages, although this is only a partial defense as some of the potions were for sexual performance and other less serious purposes)

-Cites one opinion that the Torah only prohibits animal blood but does not say anything about human blood.

-The Jew v Gentile distinction: Can't use blood from Jews but can use blood of Christian. Similar to how usury was prohibited among Jews but not between Jews and Christians. (Toaff does not mention it but you could take this a step further and argue whether the goyim count as human on par with Jews or whether goyim are some inferior species. This could also be a workaround against the prohibition against murder).

-One medieval Jewish commentator opined that because it was firmly established custom among Jews it was therefore okay.

-Various arguments about the form of the blood. It's okay as long as it's dry and/or diluted.

I think these points by Toaff blow the Torah argument out of the water.

Torture

Toaff makes a quite ingenious argument against dismissing the confessions out of hand due to torture. First, he notes that torture was standard legal practice at the time and that it was actually regulated by statute. That is to say there was a procedure to it and they were aware to some extent of the risk of extracting false confessions. While their procedures would be acceptable to us today, it is not correct to say that all confessions back then were necessarily false.

Another very strong point he makes is that, unlike most of the scholarly writing about this, Toaff has actually read the original testimonies and analyzed them in detail. Rather than dismiss them in toto as pure fantasies, Toaff notes that the details of the statements reflect the mind of the Jews, not the Christian interrogators. "In many cases, everything the defendants said was incomprehensible to the judges -- often, because their speech was full of Hebraic ritual and liturgical formulae pronounced with a heavy German accent, unique to the German Jewish community, which not even Italian Jews could understand; in other cases, because their speech referred to mental concepts of an ideological nature totally alien to everything Christian." His point here is that the details of the testimonies are very Jewish and could not have be coming from the Gentile interrogators.

Concluding Remarks

Doing a deep dive on this would be a lot of work. For any individual case (Simon of Trent, Beilis which is a fairly modern case), you could probably spend months doing research. It certainly seems like the traditional Jewish apologetics on this have not held up very well in light of Toaff's work.

Most of Toaff's work seems to deal with the broader question of ceremonial blood use among Jews rather than the question of whether people were murdered for the blood in ritual crucifixion. Toaff seems to have tried to distance himself a bit from that more explosive point, but inevitably if his work is taken at all seriously those graver charges obviously become harder to dismiss out of hand, as has been done for about a century.

I think this is still very much an open topic. The debate is far less developed than the debate on the Holocaust issue.

One thing that interests me very much about this topic (aside from it being inherently lurid and sensational) is that it creates some curious conflicts for both Jews and revisionists. If you read the Jewish apologetics on this topic, they argue that the Jews who confessed and were convicted of ritual murder were victims of coercion and that the trials were akin to witch trials. This is noticeably similar to argument revisionists make against Nuremberg and against the Holocaust. It is amusing that in this context (where they have an interest in debunking rather than defending a disputed legend) they argue in revisionist fashion for the exact sort of widespread conspiracy/mass delusion (show trials, false testimonies) that they claim is impossible in the context of the Holocaust. Similarly, for revisionists, our rationalist impulses should incline us toward skepticism of these child sacrifice stories. However, Holocaust revisionists also tend to be rightfully wary of Jewish historiography, and this "anti-Semitic" impulse in this case will push many in the opposite direction. While it may be tempting to accept the ritual murder stories essentially as a troll or just because it makes Jews mad, I think it's a very bad idea to fall into the trap of simply assuming anything damaging or embarrassing to Jews must be true, at least if you want to maintain your credibility.

If you go back a few decades (before Ariel Toaff in 2007), it seems there was near universal agreement that the "blood libel" was mythical. In the 80s and 90s, it seems that revisionists and "scholarly anti-Semites" were not attempting to rehabilitate the story and were happy to let sleeping dogs lie. From what I can tell, you have to go back to pre-WWII where you see the idea promoted by personalities like Julius Streicher. Toaff has single-handedly revived the controversy however, and now it seems a number smart people such as Thomas Dalton and Ron Unz have been convinced to varying degrees of confidence.

Perry and Schweitzer (2002)

P&S have a book called Antisemitism: Myth and Hate from Antiquity to the Present. They dedicate a 30 page chapter to ritual murder allegation. I wanted to get an idea of the state of the debate pre-Toaff, and this 2002 book seemed like a good option. The chapter is heavily footnoted although P&S have done no primary research and are merely summarizing (pro-Jewish) secondary sources. But that is the sort of survey I was looking for. Below are what I've noted as their primary arguments.

1) In many of the blood libel cases, it indeed seems that the Jews were accused falsely. In some instances, it does seem that Jews probably were scapegoated. (It would take a long time to check up on the many individual cases they discuss.)

2) They highlight the magical and superstitious tendencies of Christians in Medieval Europe. Many of the accounts indeed seem fantastic and unbelievable to modern readers.

3) They argue all the Jewish confessions ("100% of the witnesses are wrong!" as Nessie would say, lol) are invalid because of coercion and torture.

4) They argue (and this is a very old argument) that the Torah prohibits use of blood etc (Lev 17:12) and that it is therefore unthinkable and self-contradictory to use unclean blood in a religious rite.

5) They produce quotes (some from the Middle Ages) from popes etc who have made various pro-Jewish statements dismissing the blood libel charge. (There have been Catholic authorities who believed it as well. The church formally repudiated as part of the Vatican II reforms).

I think the above is a fair recapitulation of the Jewish arguments on the matter as of the early 2000s. (I don't think there have been much if any updates to their talking points).

Something that stuck out to me as I read was that they leaned heavily on flattering the reader's presumed enlightened modern sensibilities as a contrast to the primitive superstitions of those dastardly medieval Christian bumpkins. Those goofy Christians actually believed that teh jooos broke into their churches and stabbed the communion wafers and that these wafers bled like Jesus. What a bunch of rubes! They love to pile on with this sort of thing yet they conspicuously avoid any discussion of what Jews at the time believed (the implication being that Jews were immune from such irrationalism). This omission is deliberate because once you realize that Jews also had a highly magical and superstitious worldview, the charge of bizarre Jewish rituals becomes more not less believable. In other words, this argument about magic and superstition is a double-edged sword. It may limit Christian credibility but it also increases the overall likelihood of weird beliefs and rituals among both Christians and Jews.

Toaff (2007)

Toaff's commentary is distinguished by the fact that he's done serious primary source research. He knows Latin and Hebrew and all that and he relies on original medieval sources rather than the sanitized history that is produced by modern Jewish scholars. I have not yet read Toaff's entire book. I read the preface (which I would very much recommend as a quick introduction) and chapter 6, "Magical and Therapeutic Uses of Blood." That chapter caught my eye because of its relevance to the very common it's-against-the-Torah argument.

Use of Blood and the Torah

Toaff demonstrates, I think rather conclusively, that Jews (or at least some Jews) did in fact use blood (usually in powdered form) for a variety of medicinal and ritualistic purposes. A famous example that is amazingly still practiced to some extent today is that the mohel during the circumcision ceremony will suck off the blood and foreskin from the baby. This contact with blood is apparently not considered unkosher or unclean. Even worse, apparently there is a documented variation of it where the mohel would spit out the blood into a glass of wine which is then given to the baby. Toaff even notes a documented custom (keep in mind many of these things were not universal among Jews) where women would fight over the bloody foreskin, based on the superstition that eating the male flesh would bless the woman with a male child (reminiscent of our tradition of the bride throwing out the wedding bouquet). In many cases, the sources for these sorts of things are Jewish converts to Christianity (whistleblowers, if you will), and Jewish academics as a rule dismiss these sources out of hand as automatic lies. But Toaff's citations include Jewish rabbis and other Jewish sources which seem more difficult to disregard. Toaff cites examples of books with recipes and potions involving blood, e.g. mixing powdered menstrual blood in wine and drinking it to treat heavy menstruation or using powdered menstrual blood of virgins mixed in wine to treat epilepsy. It seems there was a "market" for blood and some evidence that Jews would pay good prices for this blood. (In one of the blood libel trials, it seems the father killed his son, perhaps accidentally, while trying to extract blood from the neck. His story was that he intended to sell it to the Jews.) There is even some evidence that there were "kosher retailers" of this blood since fraud was common (trying to pass of animal blood as blood of a child).

Ah, but how do we square all of this with the supposed prohibition in the Torah? I didn't find the Torah argument convincing to begin with since legal rules are not much of a barrier to a people who are famous for creative and flexible legal interpretations (e.g.). Toaff helpfully confirms my suspicions by supplying direct examples of some of the many rationalizations (talmudry) that have been offered over the centuries.

-There are exceptions for cases of life and death (could justify some of the health usages, although this is only a partial defense as some of the potions were for sexual performance and other less serious purposes)

-Cites one opinion that the Torah only prohibits animal blood but does not say anything about human blood.

-The Jew v Gentile distinction: Can't use blood from Jews but can use blood of Christian. Similar to how usury was prohibited among Jews but not between Jews and Christians. (Toaff does not mention it but you could take this a step further and argue whether the goyim count as human on par with Jews or whether goyim are some inferior species. This could also be a workaround against the prohibition against murder).

-One medieval Jewish commentator opined that because it was firmly established custom among Jews it was therefore okay.

-Various arguments about the form of the blood. It's okay as long as it's dry and/or diluted.

I think these points by Toaff blow the Torah argument out of the water.

Torture

Toaff makes a quite ingenious argument against dismissing the confessions out of hand due to torture. First, he notes that torture was standard legal practice at the time and that it was actually regulated by statute. That is to say there was a procedure to it and they were aware to some extent of the risk of extracting false confessions. While their procedures would be acceptable to us today, it is not correct to say that all confessions back then were necessarily false.

Another very strong point he makes is that, unlike most of the scholarly writing about this, Toaff has actually read the original testimonies and analyzed them in detail. Rather than dismiss them in toto as pure fantasies, Toaff notes that the details of the statements reflect the mind of the Jews, not the Christian interrogators. "In many cases, everything the defendants said was incomprehensible to the judges -- often, because their speech was full of Hebraic ritual and liturgical formulae pronounced with a heavy German accent, unique to the German Jewish community, which not even Italian Jews could understand; in other cases, because their speech referred to mental concepts of an ideological nature totally alien to everything Christian." His point here is that the details of the testimonies are very Jewish and could not have be coming from the Gentile interrogators.

Concluding Remarks

Doing a deep dive on this would be a lot of work. For any individual case (Simon of Trent, Beilis which is a fairly modern case), you could probably spend months doing research. It certainly seems like the traditional Jewish apologetics on this have not held up very well in light of Toaff's work.

Most of Toaff's work seems to deal with the broader question of ceremonial blood use among Jews rather than the question of whether people were murdered for the blood in ritual crucifixion. Toaff seems to have tried to distance himself a bit from that more explosive point, but inevitably if his work is taken at all seriously those graver charges obviously become harder to dismiss out of hand, as has been done for about a century.

It seems that after the controversy over his book (the first edition was pulped), Toaff has decided to hold back a bit and stick to very narrow claims.He came to international prominence with the 2007 publication of the first edition of his controversial book Pasque Di Sangue (Passovers of Blood), in which he claimed historical basis[1] for ritual use of human blood, obtained by murder. The claim was criticized as lending support to blood libel, an allegation that modern historians have described as unsupported by facts and which the Catholic Church has similarly repudiated since the 13th century.[2][3] Toaff wrote that these critics had misunderstood his book, which argued that the ritual use of small quantities of dried blood in magical curses had been a real practice among medieval "Ashkenazi extremists", but that this was unrelated to the accusation of ritual murder which was the central claim of blood libel.[4]

I think this is still very much an open topic. The debate is far less developed than the debate on the Holocaust issue.