First let me point out that in the few instances where Rudolf gives a quantitative length of time for PB formation, it is very short: "within 48 hours" (p.190), "after 30 min", "after a few minutes" (p.194), "in minutes" (p.196). In the longest case, Rudolf ran a 120-day experiment in which PB did not visibly form (p.327f). All of this is

suggestive that the normal time span for this process is minutes, maybe days, not years.

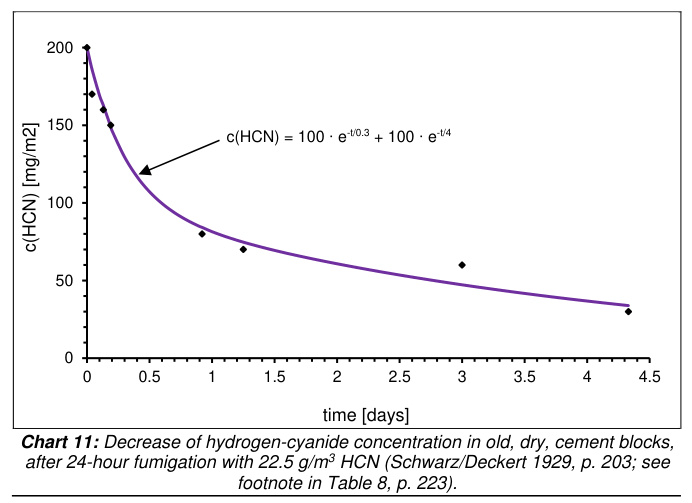

Second we should consider Schwarz/Deckert 1929, a study which actually measured how much HCN lingered in cement and concrete after fumigation and ventilation. Note that Rudolf in discussing this characterizes "three days" as a "longer period of time" (p.224), which again suggests the quantity of time under consideration. In testing "Cement Mortar, well-dried and set", the HCN concentration was found to fall continuously until they stopped testing, reaching 15% of the initial HCN concentration at 104 hours. Rudolf worked out a formula and chart for the cement data, as pictured (p.225):

- falling HCN chart 11.png (39.25 KiB) Viewed 82 times

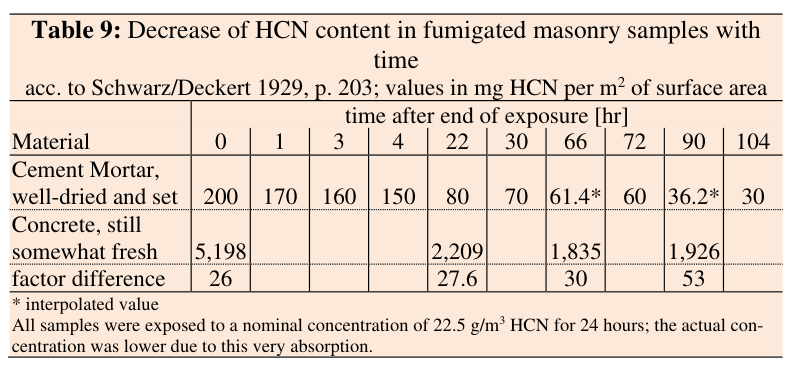

The HCN concentration in "Concrete, still somewhat fresh" was similarly found to drop by half within 22 hours and further after. Presented as a table (p.224):

- falling HCN table 9.png (67.17 KiB) Viewed 82 times

Rudolf expresses some reservations in this data, and I have more. Only four data points are given for concrete, and since the fourth one shows an increase there must have been measurement error or imprecision.

Still, it does suggest a curve which flattened quickly. Rudolf interprets this as a possible indication of the HCN having been converted to other forms. He writes "their HCN content doesn’t seem to drop anymore at all after some 3 days. It seems to have been chemically bound." (p.225) I'm not sure this follows logically. If the HCN was chemically bound then it was no longer strictly HCN. And that would mean the high HCN content measured might to a great extent have represented cyanide compounds which were

reverting back to HCN. Or perhaps this is merely a semantic problem that can be disregarded.

Let me now return to the above quote where Rudolf wrote PB precursors could "remain in a stand-by position, pending a drop in the pH value". How long could those precursors actually remain? To my surprise, it does seem possible that they could stick around for years, even if Rudolf doesn't say so explicitly. This is because hexacyanoferrate(II) (and also calcium cyanide, I believe) will remain highly stable as long as the wall remains highly alkaline and at least a tiny bit humid. In that environment the PB precursors are "favored" over HCN. For what it's worth, Grok AI seems to confirm these facts.

However there is a big caveat. Prussian Blue is only formed where the concrete has become less alkaline. Concrete does not dealkalize in uniform. It dealkalizes along a zone of carbonation which very gradually moves from the surface to the interior. Where and when carbonation occurs, what was alkaline becomes more neutral, and all these precursors should begin to revert to HCN except where they convert to PB.

Since we are discussing surface stains, we are concerned with the part of the wall that was carbonized

first. Since the wall did not form PB by 1944 or even 1946, it would seem that any near-surface cyanide compounds reverted to HCN and diffused into the environment.

Alternatively, maybe there is some mechanism by which cyanides in the center of the wall could be brought to the outer layers and concentrated in a narrow spot, but this remains unexplained and opens other difficult questions, like why didn't the stains appear on the interior side?

This is probably the extent to which we can go with TCOA. Someone else's writings or photographic material from another location could take this discussion further, but I can't find anything that would be relevant.