A Study of the Cyanide Compounds Content In The Walls Of The Gas Chambers in the Former Auschwitz and Birkenau Concentration Camps

https://phdn.org/archives/holocaust-his ... port.shtml

The Numbers

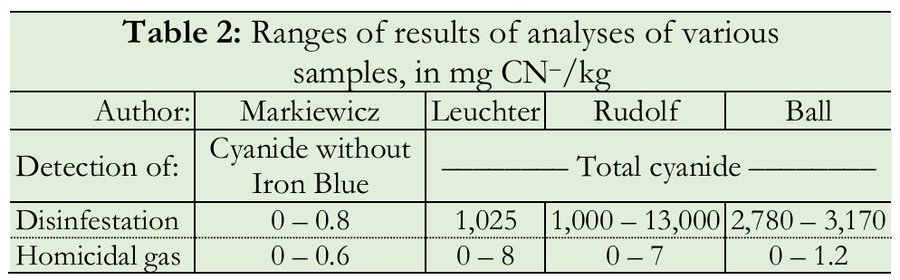

One thing you will notice is that Holocaust defenders will talk in circles about this topic, but they never show you the actual numbers. This is because the numbers are so dramatic they cut right through a lot of their spin.

First thing to notice is that the Markiewicz results are really low, even for disinfestation gas chambers. That defies common sense. If we have a room where we know Zyklon B was used regularly and the walls are covered with Prussian blue, we should expect to find some cyanide compounds! If their test can't detect cyanide in a room where there's so much cyanide that we can see it, then it's not an adequate test. Period. According to Markiewicz, a room like the one below barely has any cyanide.

Outrageous Explanations

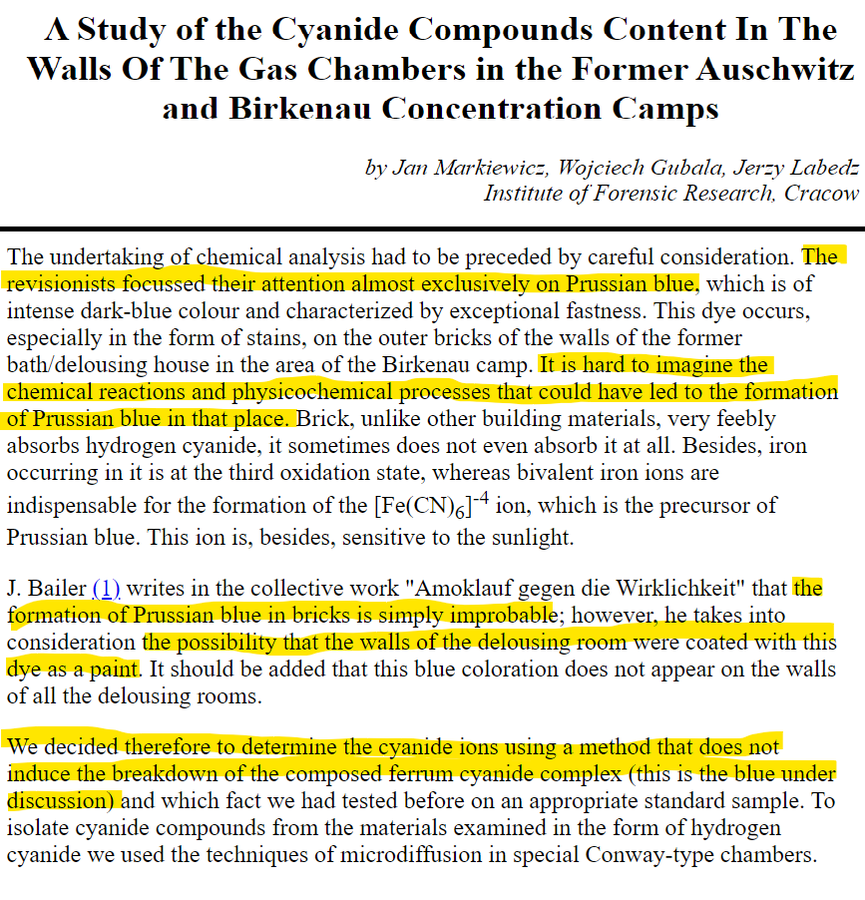

Here is the explanation they give for whey Prussian blue shouldn't be included.

They are just outright lying here. They know damn well why there's Prussian blue in the fumigation chambers. It's because Zyklon B was used in those rooms and, under the right conditions, the HCN in the Zyklon will react with iron present in the walls. And that's what happened. To suggest that this is "hard to imagine" or that perhaps it's blue paint is ridiculous to the point of being insulting.

If they were honest, they would have admitted that there is a massive difference between the actual gas chambers and the alleged gas chambers. From there, they could have tried to come up with technical reasons why the Prussian blue didn't form in the latter. But to rig the test in order to deliberately obscure a difference that is obviously there is simply dishonest.

Stability of Prussian Blue

Another significant point is that Prussian blue is very long-term stable. Once it forms, it's hard to get rid of. Here is what James Roth, the chemist who tested Leuchter's samples, said at the Zundel trial.

https://www.ihr.org/books/kulaszka/34roth.htmlRoth was shown Exhibit 144, a colour photograph of the blue staining on the wall of Delousing Facility No. 1 at Birkenau from which sample 32 had been removed. He indicated that the blue colour was what was commonly referred to as "Prussian blue." (33-9289) The chemical definition of Prussian blue was ferro-ferri-cyanide. (33-9297) Prussian blue was an iron cyanide produced by a reaction between iron and the hydrogen cyanide. It was a very stable compound which stayed around a long time. If hydrogen cyanide came into contact with bricks or mortar containing iron, it was fully conceivable that a reaction of the iron and hydrogen cyanide would take place, leaving behind the Prussian blue. (33-9290) In porous materials such as brick and mortar, the Prussian blue could go fairly deep as long as the surface stayed open, but as the Prussian blue formed, it was possible that it would seal the porous material and stop the penetration. If all surface iron was converted to Prussian blue, the reaction would effectively stop for lack of exposed iron. (33 9291)

Roth testified that the iron/cyanide reaction capabilities of samples 9 and 29 were no different from that of sample 32. If samples 9 and 29 had been exposed continually everyday for two years to 300 parts per million of hydrogen cyanide, Roth testified that he would expect to see the formation of the iron cyanide compounds; the so called "Prussian blue" material, in detectable amounts. The reaction of the two substances was an accumulative reaction; the reaction continued with each exposure. One way for this reaction not to occur would be a lack of water. These reactions, in many cases, required water or vapour in order to occur. However, in rooms of normal temperatures and normal humidity, there would be plenty of moisture present for this type of reaction to take place. (33-9293, 9294)

Prussian blue did not normally disappear unless it was physically removed. To be removed from a porous material like a brick it would have to be removed by sandblasting or grinding down the surface or by the application of a strong acid such as high levels of sulphuric, nitric or hydrochloric acid. It would be more difficult to remove from porous surfaces because of the fact that the formation would have taken on depth. (33-9297, 9298) This ended the examination-in-chief of Roth, and his cross-examination commenced.

"Anything Above Zero Proves It's a Gas Chamber"

I've have seen this argument online. People will say (without showing you the actual numbers, of course), that they "found cyanide" in the homicidal gas chambers, i.e., there were some non-zero samples. They are seriously trying to hang their hat on 0.6 parts per million.

1) Do these people not understand how little <1 ppm is?

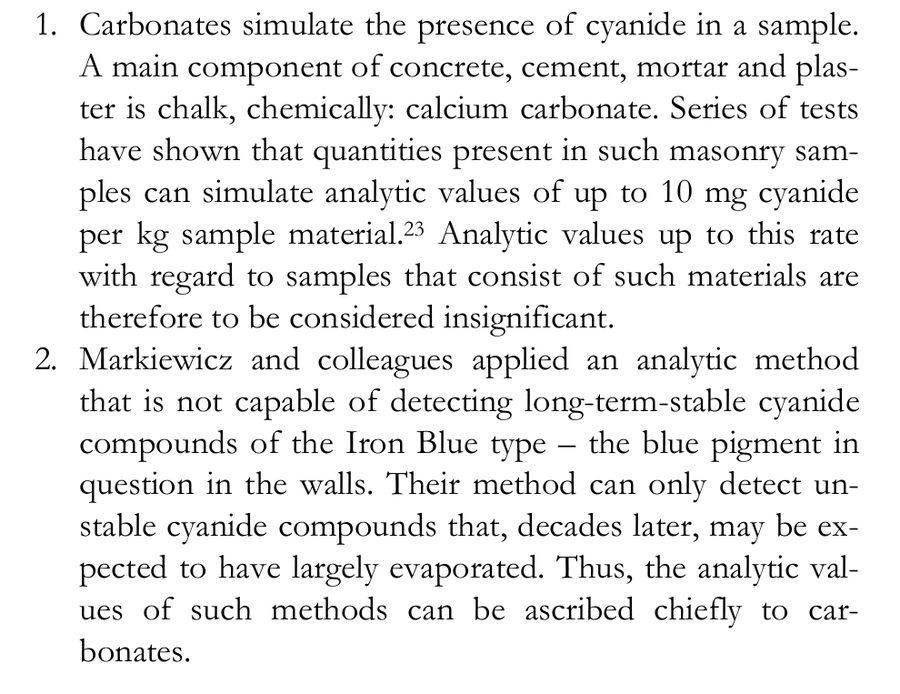

2) You will get tiny amounts like that even in random rooms

3) Small values can be due to carbonates (see below)

Cyrus Cox, Auschwitz Forensically Examined, pg. 37

Nonsense Arguments in the Wild

This stuff came up the other day on X and there was some clown on there who made the following very poor arguments, among others.

-Leuchter's samples were too "diluted"

-Leuchter "lied" to the lab about the samples

-Leuchter was not a historian and hadn't spend enough time in the archives

It's hilarious to complain about sample dilution while simultaneously defending Markiewicz whose results are near zero. Dilution would bias the results downward. This means Leuchter's readings for the fumigation chamber samples would be too low. In fact, Leuchter's method worked just fine for finding cyanide, if it was actually there. Saying Leuchter "lied" to the lab is just silly. Blind testing is better scientific practice. If they don't know what it is, they will be objective. If the people testing know it's from Auschwitz, there would be pressure to get the "correct" result. Leuchter's lack of knowledge of Auschwitz at that time is also not terribly important. As if you need to be an expert Auschwitz historian to chip off wall samples and put them in bags. Faurisson and others were there to help him know what rooms were relevant. That basic historical knowledge was all that was needed for the sampling.

These arguments are what you might call the "throw spaghetti at the wall" approach.